In the localisation industry we frequently come across misconceptions about the Chinese language, where and how it is used, and other queries relating to Chinese culture. Being a Mandarin speaker and card-carrying Sinophile, I feel duty-bound to try to set the record straight and try to end the confusion if I can, so intend to do this through a series of blog posts and other articles that we’ll share with you over the next few months.

Feel free to comment and ask any questions you’d like answered or have always wondered about – I’ll do my best to answer!

Without further ado, here is my response to the most common question that arises: Which type of Chinese do I need?

You may have heard various names used to refer to the Chinese language, including Mandarin, Cantonese, Taiwanese, Simplified Chinese and Traditional Chinese. All of these do exist, and refer to slightly different things.

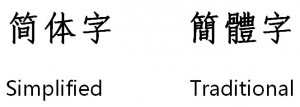

We’ll start with the most straightforward part.There are just two forms of written Chinese: Traditional and Simplified. Traditional Chinese, as the name suggests, is more established, and was the sole method of writing all varieties and dialects of Chinese until the 1930s, when language reform in mainland China first began.

The language reform driven by Mao Tse-Dong and the Chinese Communist Party in the 1940s saw the creation of simplified versions of thousands of characters by reducing the number of components each one is made up of – i.e. how many pen strokes it takes to write it.

This simplification can be considered similar to an abbreviation of a word in English such as abbreviation > abbrev. or does not > doesn’t. I have heard Simplified Chinese compared to textspeak, which is incorrect and quite offensive! Simplified Chinese is by no means an inferior version of Chinese, nor should be considered as such.

So, which one do you need? It depends on the country you are trying to communicate with.

Mainland China/The People’s Republic of China: Simplified Chinese

Simplified Chinese is the standard written form of Chinese in use in the People’s Republic of China. For example, someone in the North-East of England speaks differently to someone from London, but they would be able to read and understand the same books, newspapers, websites, etc.

Mandarin refers to the dialect of Chinese most widely spoken in the North of China, and so has become the universal standard.

In other regions of the country, other dialects are spoken, much like in any country, but Mandarin is widely understood.

Hong Kong: Traditional Chinese

Cantonese was the main dialect of Chinese spoken in Hong Kong while it was under British rule. Since the return of the colony to the People’s Republic of China, a “biliterate and trilingual” policy has been adopted, which gives Chinese official language status alongside English. Cantonese is recognised as the official spoken variety of Chinese in Hong Kong, but Mandarin is also accepted, and growing in importance.

Taiwan: Traditional Chinese

Taiwanese is written using Traditional Chinese characters, but when spoken most closely resembles the Mandarin dialect.

Because Taiwan is separate from both China and Hong Kong, the language has developed in a slightly different way there, making the written form mutually unintelligible in many cases, and so texts written for Hong Kong will not usually be suitable for a Taiwanese audience.

The short answer is that if you are reaching out to a global audience, you should really use both written varieties. If you are targeting Taiwan in particular, then a third version may also be a good idea to maximise the results of your campaign or website.

I hope this has helped to clarify the situation, but don’t worry if you’re still unsure. Just get in touch and we’ll be happy to advise you.

10 February 2014 11:49